new frontiers

The Future of Communication is Multimodal

regaining a voice

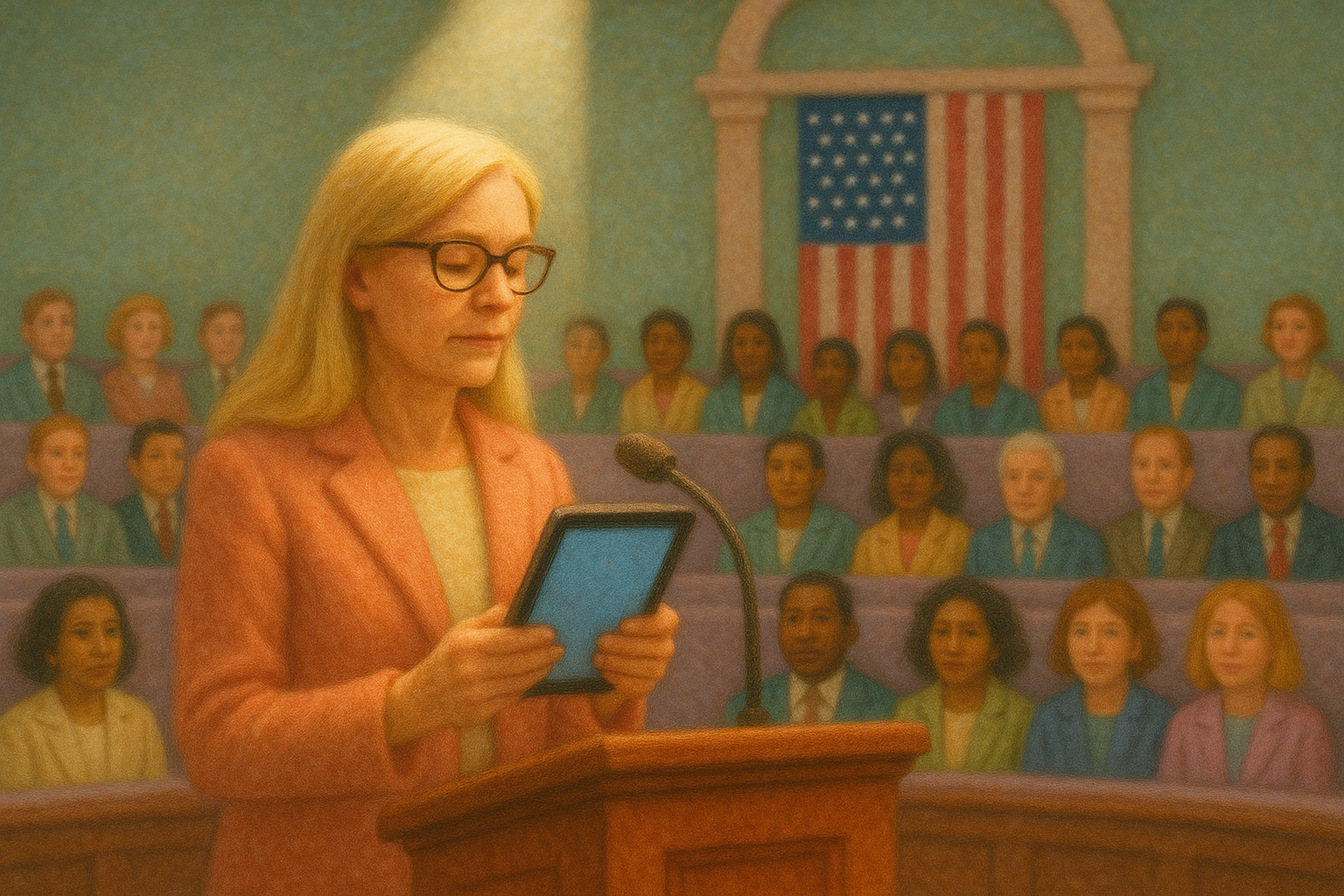

On July 25, 2024, Representative Jennifer Wexton rose at the House lectern with a tablet. When she tapped the screen, an AI-cloned version of her own voice, built from years of public recordings, delivered her speech on disability pride. A neurological disease had eroded her natural speech, but AI technology amplified her voice in the House once again.

It was the first AI-voiced address in congressional history. In a chamber that has canonized the art of oratory for more than two centuries, Wexton’s speech was more than an accommodation; it was redefining what counts as a congressional delivery. Her speech was celebrated as a breakthrough for accessibility, but for people who have used assistive, multimodal technology for years, this is nothing new.

disability aids or general tools?

Reading this quickly, it would be easy to assume Wexton was using assistive technology. But the tool she used was not a specialized augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) device. It came from ElevenLabs, a mainstream AI voice company with a mission to make all content universally accessible, while working with non-profits and AAC platforms to integrate their products meaningfully. Washington calls it innovation, but it’s just catching up.

Long before a synthetic voice entered Congress, disabled communities had been building rich multimodal languages of their own. For decades, AAC users have been stitching together text, emojis, GIFs, and synthesized voices into full conversations, fluent in multimodality decades before it became one of the most talked about Generative AI trends of 2025.

What happens when historic institutions finally co-sign tech that accessibility communities have been exploring for years?

new forms of access + embodiment

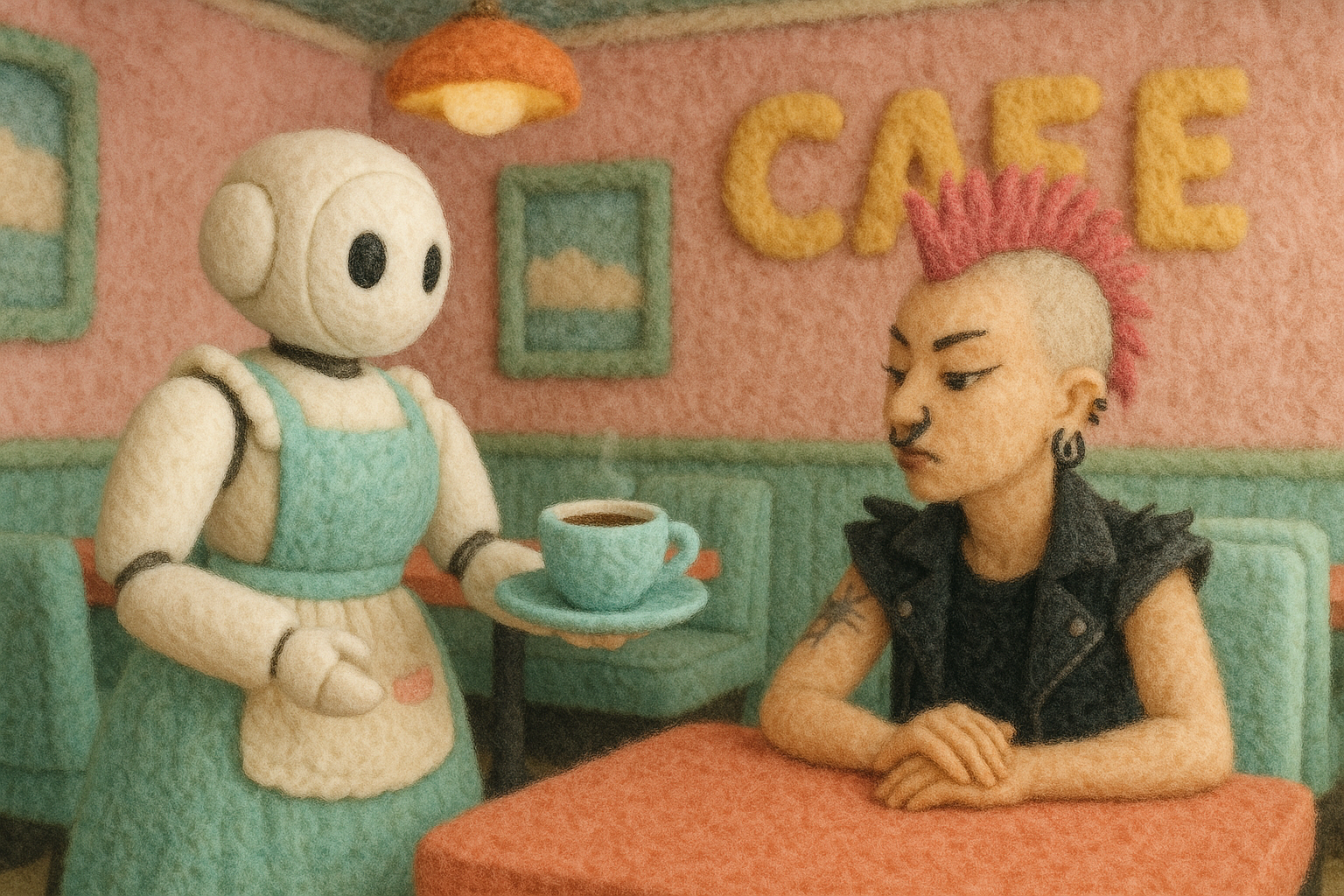

Across the Pacific, at a Tokyo café, a four-foot robot glides between tables taking orders. It has a human ‘pilot’ who is working from home, immune-suppressed after cancer treatment, operating the OriHime avatar through a tablet. At Dawn Avatar Robot Café, dozens of workers log shifts from hospital beds and living rooms. Their disclaimer on the website: “We are not operated by AI.”

This kind of multimodal presence is entering mainstream business culture as well. What once read as ‘specialized’ tech is now the grammar of modern work. Avatars in video calls. Digital twins at board meetings. AI note-takers.

If the 1990s gave us the “curb-cut effect”—design originally for wheelchair users benefiting strollers, travelers, and delivery workers—the 2020s have given us the “caption effect.” Captions, once considered accommodations or relegated to foreign films, are now the cultural default.

.png)

choose your own access + modality

Nearly two-thirds of Americans under thirty now watch television with subtitles, not because they can’t hear but because they understand more easily. More than a hundred studies confirm that captions boost memory, attention, and literacy for children, students, and adults alike. When we ‘other’ accessibility needs, we miss out on the benefits of cultural innovation.

What the tech industry calls “multimodality” is actually the mainstreaming of practices born as access: captions, transcripts, avatars, computer vision. NVIDIA experiments with AI sign-language tutors; Apple now ships iPads with eye-tracking built in.

For neurodivergent people, multimodality is already survival. When meetings pile up, AI transcription steps in. Task-breaking apps scaffold executive function. Custom GPTs translate neurotypical subtext into plain language. These are not niche hacks. They are power-user adaptations.

accessibility communities: the frontline of multimodal tech

Some might frame accessibility communities as uniquely vulnerable to AI deception. In truth, their fluency in adaptation makes them the sharpest stress-testers of new tools, quick to surface both risks and possibilities.

For accessibility communities, the stakes are high: their agency depends on systems that can drift out of tune (AI voice drift) or fail to safeguard the confidentiality of their data. In a world that withholds consistent support, the allure of dedicated tools is powerful—which is exactly what makes AI both compelling and potentially risky.

As multimodal tech races ahead, we should keep in mind the users at the sharpest edge of the signal—disabled, neurodivergent, and those navigating mental health—who have long been the first to evaluate these systems.

Tech companies bear a responsibility to think more carefully about their accessibility communities, who are often first to adopt, be dependent, and vulnerable. They must design accessible tech inclusively, respect community knowledge, and not add more prescriptive 'norms' that reduce communication diversity.

Universal fluency represents a fundamental shift: the AAC market is set to double to $3–5B within the decade, and AI avatars are on track for $100B+ by 2034. Institutions that fail to recognize this shift miss the deeper story about what’s really driving communication forward.

And in order to move forward, we must learn from the past. The content of every new medium, McLuhan reminded us, is always an older medium. The content of multimodal AI isn’t just code; it is generations of ingenuity from those excluded from binary communication norms: speech transcribed to gesture, text mapped to touch, images translated to sound.

McLuhan predicted a “global village.” Accessibility communities have been building one for decades - not for digital efficiency, but for the simple right to be heard and seen.

So when the House quiets for a cloned voice; when teenagers subtitle everything they watch; when workers beam into cafés through avatars—we are not watching disabled people catch up.

We are watching the future concede that the margins were always the center.